At DevResults, we've come to believe that conventional processes for setting salaries are not only arbitrary, but provide excellent hiding places for bias and prejudice—leading to gender and racial pay gaps. So we've decided to no longer negotiate salaries or raises. Instead, we use a spreadsheet model to calculate everyone's salary, based on their experience, education, and tenure.

At our team retreat in February 2019, we decided that we would be internally transparent about salaries at DevResults.

We were motivated to do this by two things:

The first was a practical matter: We want everyone on the team to have the information they need to make good decisions. (Which, after all, is what this company is all about!)

From the beginning, the entire team has been involved in making big strategic and operational decisions. We're all responsible for the financial health of the company, and so we all need to have access to the company's numbers. It's hard to do that if the details of the company's biggest expense—staff salaries—are treated like a state secret.

The second consideration was even more important: We wanted to make sure that we're not inadvertently contributing to racial or gender income inequality, and transparency was the obvious first step in that direction. After all, if we believe we're paying people fairly, then we have nothing to hide. And if we're not paying people fairly, the first step towards correcting that is for us all to look at the numbers together.

Quantifying fairness

Once salary numbers were public within the company, we started to talk about what adjustments needed to be made to make compensation more fair.

Fairness turns out to be much easier to recognize than define.

When any of us thinks about what someone "ought" to be paid, there are a lot of things to take into consideration; and no two people will weight different factors the exact same way.

- How much do things like seniority, education, or experience affect salaries?

- How do we value career experience that's not directly applicable to a particular job?

- Should we consider differences in employees' financial needs - like the number of dependents they have, or the cost of living where they are?

- Do we care more about being equitable or about paying market rates?

There's no way to get around the fact that (a) there are a lot of different variables, and (b) there's no objectively correct answer to which variables we should take into account, and (c) how they should be weighted.

One response to this inherent complexity and subjectivity would be to just throw up our hands and decide that there's no way to be logical about salaries.

But then how do we even have a conversation about fairness? If Alice's salary is $1,000 or $10,000 or $50,000 lower than Bob's, is it unfair, or is there a good reason for it? And if there's a good reason, what is it? What salaries would be fair for Alice and Bob? The answer will always involve some combination of factors like the ones listed above.

If you have opinions about what different people ought to be paid, you're working from some kind of mental model. And it's better to make that model explicit than to keep it in your head.

We quickly came to the conclusion that we needed a model — a mathematical encapsulation of our collective thinking about what's fair.

I see this as the logical conclusion of salary transparency, not just transparency for what people are paid, but for what our assumptions and values are. Whatever we come up with might not align perfectly with any individual's exact preferences, but at least the individual components will be out in the open for everyone to see.

How we came up with a model

Needless to say, few workplace topics are more anxiety-producing than compensation, and as soon as we started talking about coming up with a fundamentally new salary model, you could feel the aggregate cortisol levels rising.

I invited everyone on the team to submit a spreadsheet with a salary model that seemed fair to them, and to work out the salaries that this would predict for themselves and their colleagues.

We then looked at these different models together and talked about their different assumptions and weightings, and the values that they represented. Here are some of the most important questions we had to wrestle with:

Do we value different roles differently? I'd always assumed that programmers were more expensive than people in other roles. When I actually dug into market data, though, it was hard to find statistical justification for that. In the end we decided that we wouldn't take roles into account; all else being equal, an engineer is paid the same as someone working in data science or business development.

Do we adjust for cost of living? We're a distributed company. Some of us live in pricey cities like Washington, DC, others live in parts of the country where things are less expensive. A couple of us live in countries with completely different economies and markets from the US. We ultimately decided that we didn't want to penalize people for where they live, or or set up incentives for or against moving somewhere else.

What about things like number of children or other dependents? Some salary models we looked at take into account the size of the employee's family. After some discussion, we came to the conclusion that having more or fewer kids, like deciding where to live, was just one of many lifestyle factors that affect people's cost of living, and that didn't want to be making judgments and giving financial rewards for some choices and not others.

How do we value education? As a software company, we've always been skeptical of academic credentials. Some of our best software engineers never graduated from college; neither did Steve Jobs, Albert Einstein, or Oprah Winfrey. On the other hand, it would be absurd to say that education doesn't have value. For many of us, what we learned at university or grad school directly contributes to our effectiveness. In the end, we decided to value the time spent in post-secondary education as a form of experience.

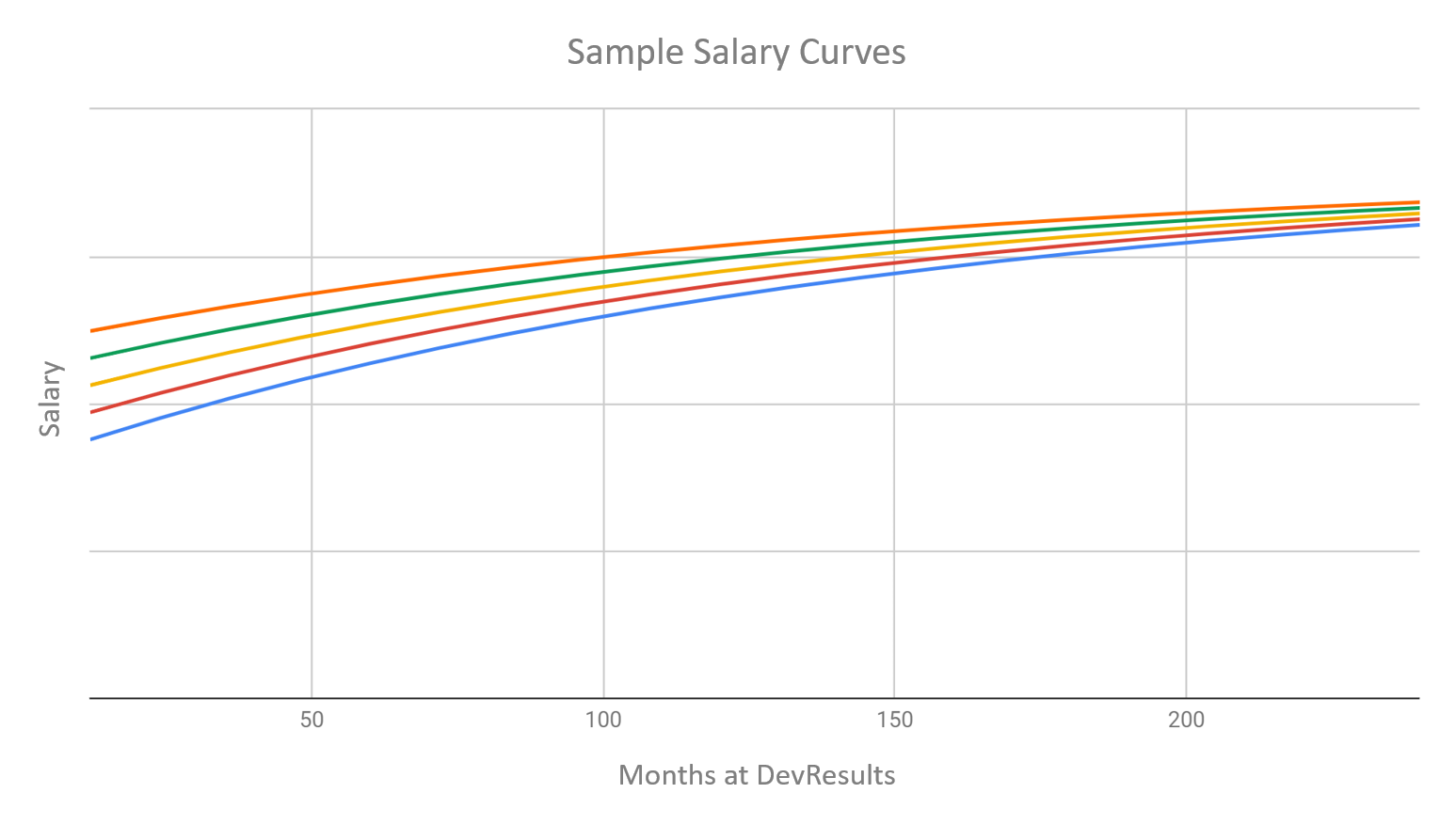

How do we value tenure (time working here) relative to time working elsewhere? It's often easier to get a big raise by getting hired at another company than by getting promoted internally. We'd like not to incentivize people to leave in search of better pay, so we value time at DevResults higher than the equivalent experience elsewhere.

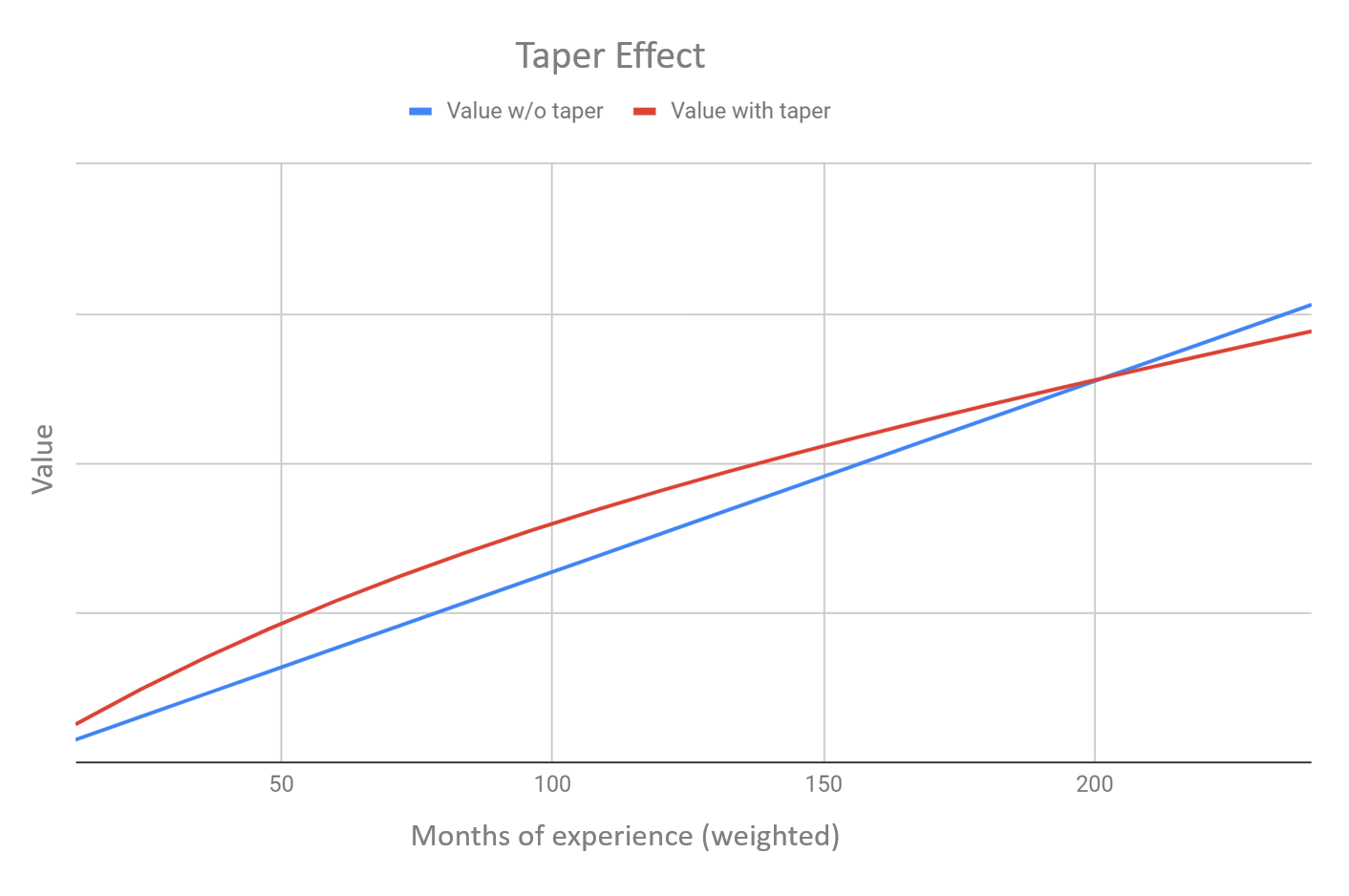

Does the value of experience keep climbing indefinitely at the same rate? Intuitively, it seems obvious that you learn more in your first year on the job than you do in your tenth year. So we built a tapering mechanism into the model, both for experience/education and for tenure.

Should pay be based on performance? In theory, it makes sense that high performers should be rewarded. In practice, we don’t have a good way to quantify differences in individual contributions. Instead, we’ve put in place a bonus system that is based on the company’s overall financial health and on other metrics that we work towards together as a team. .

Our current salary model

The salary formula we ended up with is a function of each person's work experience, education, and tenure at the company.

The only factor determining a person's starting salary is months of experience and education. The categories and corresponding weights we ended up with are:

- Experience (relevant)

- Experience (partly relevant)

- Experience (other)

- Education (relevant)

- Education (other)

In our model, we weighted these factors from 70%-200%. These weights are applied directly to the corresponding time, so 4 years of "other" experience counts the same as 3 years of relevant experience, etc. The experience/education metric is then multiplied by a factor that decays asymptotically, so that the first years of experience count more than later years. For example, the first year of experience adds about $5000 to the starting salary, while the 20th year adds about $2000.

Year-over-year changes to an employee's salary over time are entirely driven by another asymptotic curve. The formula for annual increases is set up in such a way that lower salaries rise more quickly than higher salaries, so that two people with different starting salaries will see their salaries converging over time. In practice the nominal (not inflation-adjusted) annual increase for someone making $80,000 would be nearly 10%, while the annual increase for someone making $150,000 would be less than 2%.

Each year, the numbers in our model are updated for inflation using the trailing 12-month percentage change in the official US consumer price index (CPI) for January of that year.

Before you try this at home ...

Keep in mind that there's nothing transcendentally true or correct about the inputs or outputs of our model. The formulas proposed by different team members all were reasonable for the most part, but the outputs varied widely. We basically just fiddled with the knobs until we came up with something that seemed fair to everyone.

This is an experiment, and we're still in the early stages. We've only had this model for less than a year, and — importantly — we haven't hired in that time; so this system hasn't been measured against the job market, which will be an important test.

So we'll see how it goes. We intend to iterate on this on an annual basis, and we'll always be open to rethinking it again from first principles. Nevertheless, it's hard for me to imagine going back to a system where salaries are primarily determined by the negotiating skills of the people involved.